SOURCE: The Guardian.

There has never been a greater degree of uncertainty surrounding the future of video game consoles – or has there? Does the great crash of 1983 hint toward our future?

Atari blew it. At the start of the eighties, the manufacturer of the world's best-selling console allowed its market to be flooded with mediocre games, published by reckless and cynical third-parties. Meanwhile, the company over-hyped and over-manufacturered its own monstrosities, the likes of ET and the awful VCS conversion of Pac-Man produced in their multi-millions. Then in 1983, amid other contributing factors, the console industry collapsed.

And now, just as the economy is

beginning to resemble the mess of the early '80s, so is the console

business. It is an age of hubris and panic. While Nintendo has invested heavily in the dual-screen entertainment dream, pitching its Wii U console at families who watch TV while tapping away on tablet computers, Sony and Microsoft

both seem to be flirting with a future in which the next-gen consoles

become set-top boxes of mass, digitally distributed entertainment. It's

domination or death. It's 1983.

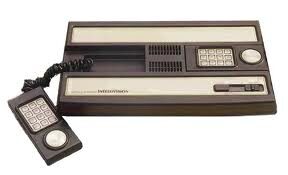

The specifics are very different but the patterns are familiar. In '83, we were looking at a saturated console market. There were too many machines competing with each other, vying for consumer interest – the Atari VCS, the Colecovision, the Intellivision... And right now, if you include handheld devices, we have too wide an array of platforms once again. Arguably, the most stable years for the console games business – the mid-ninties to the mid-2000s – were dominated by one machine, the PlayStation. There hasn't been an era since the early '80s in which three consoles and their handheld offshoots have battled it out so closely.

Another similarity between the two periods is the encroachment of a disruptive new presence. In the '80s that was the dawn of the home computer – the Commodore 64, the Apple II, the Spectrum – machines that offered much wider functionality to a broader user base at comparable prices. In 2012, the disruption is coming from smartphones, tablets, smart TVs... all offering wider functionality to a broader user-base at comparable prices.

Even the attempt to harness new information infrastructures echoes back to this period. The Atari Gameline and Intellivision Playcable both sought to bring downloadable gaming and linear content services to consoles. Even then, there was an understanding that digital consumption of varied content was the future.

It's interesting that veterans of the eighties industry are re-grouping and re-assessing now. On Wednesday David Darling, founder of publisher Codemasters, wrote a blogpost on the site of his new indie digital gaming company Kwalee about the "Jurassic" console business, and the need for Sony and Microsoft to abandon old distribution methods:

Sony and Microsoft cannot let the retailers dictate game prices going forwards if they want to break free from the current over-priced model, their next consoles, PlayStation 4 and Xbox 720 need to be digital only, or they will fail. Once Apple add an App Store to Apple TV they could take over the living room games industry like they have taken over the handheld games industry with the iPhone and its flexible pricing and lack of distribution costs. The industry is transitioning from boxed to digital games.

If the next generation consoles have media drives like DVD to keep distributors and retailers happy so they can sell physical product this will make the machines uncompetitive. They will not be able to compete on price. The retailers will say to Sony and Microsoft: "You can't sell game X at retail for $60 and then sell it in your App Store for $2." However, console-makers will need to sell games for $2 or else they will not be competitive with Apple. Nintendo 3DS and Sony Vita are not currently competitive with iPhone and Android game prices.

Meanwhile, on a much grander scale, Dave Perry has sold his Gaikai cloud gaming company to Sony for $380m. Perry started out in the early eighties coding games for the likes of Virgin and Mirrorsoft, and may now have a significant role in where consoles are heading. In a fascinating analysis of the purchase, Digital Foundry's Richard Leadbetter, sees a future in which streamed gaming services sit beside traditionally delivered titles, offering true cross-platform gaming across Sony's array of platforms:

Far from replacing existing consoles and simply streaming those games over IP, we could see the emergence of a brand new format, capable of experiences with a size and scale, and levels of interconnectivity we've never played before – games that could run on all of Sony's existing consoles, its HDTVs and PlayStation-certified mobile phones. Think about this for a moment: a Naughty Dog or Sony Santa Monica game built from the ground up, designed with cloud hardware in mind? The possibilities are mouth-watering.

This sense of Sony including its other consumer technology products into the streaming content eco-system is an important one. It's something picked up by analyst Piers Harding-Rolls at Screen Digest in another interesting report:

This extending strategy will be relevant to other connected Sony devices or even possibly to third-party devices if it makes commercial sense to the company, although at this stage it is clear that the company's priorities are to support sales of its own devices. As such Gaikai's technology is important in supporting Sony's TV division, which is under particular commercial and competitive pressure at the moment. IHS Screen Digest's forecast of over one billion active connected TV devices across the world by the end of 2016 underlines the significance of this device category for future entertainment content distribution including games.

Microsoft's strategy with SmartGlass – its smartphone and tablet app capable of organising cross-platform connectivity with the Xbox console – is comparable, although for the Seattle giant it's more about pushing Windows 8 and forging a route into the smartphone and tablet markets. Both Gaikai and SmartGlass are about building an inclusive entertainment architecture in which the console is both the server and the service; the hub world in a integrated entertainment universe. Analysing the SmartGlass technology for MCV, Michael French wrote on Wednesday:

Microsoft knows that the market is moving on beyond the console, and moving onto devices it can never hope to dominate. And it has to follow. When an Xbox exec says 'we'll go wherever our users are', that isn't actually aspirational nonsense – it's a concession to the fact that Microsoft's users aren't just users of Microsoft's operating systems. They own devices that have software from sworn enemies Apple and Google.

There are interesting rumours, too, about the next Xbox console. Microsoft has wrangled the Xbox 8 domain from a cybersquatter, leading to suggestions that this is the name of the company's next machine. Some have suggested this is an alignment with the Windows 8 OS, but put 8 on its side, goes the alternate line of conjecture, and you have the symbol for Infinity.

Many have predicted that the next console generation will be the last (read our interview with Crytek founder Cevat Yerli). And that has always taken on an apocalyptic tone. But it could also mean that what Sony and Microsoft are currently building are boxes designed to be endlessly updated and reconfigured. Instead of annihilation, evolution.

In 1983, the console business was almost destroyed by poor software quality control and an inability to establish more diverse entertainment offerings. Back then, the disruptive factors were cheap PCs and the first hints of an internet business. Now, console manufacturers have infrastructures built to embrace online distribution, they understand quality control and they have smartphones and tablets.

The question is about how far they are willing to evolve: will the future of consoles be about hybrid services – with physical games existing beside downloadable and streaming products? Or will be see a major leap away from boxed goods entirely and into a solely digital future? If this isn't the end, is it really a beginning?