A framed menu from Toots Shor, the famed Midtown New York saloon and restaurant, once hung on the wall above the desk of George Plimpton, the patrician writer and Paris Review founder whose name became synonymous with “participatory journalism.”

For decades the restaurant had been a hangout for celebrities—Frank Sinatra, Jackie Gleason, Charlie Chaplin, Joe DiMaggio, and Marilyn Monroe. Plimpton’s menu, from the winter of 1967, advertised a shrimp cocktail for $2.25 and an order of chopped chicken liver for $1. At the top of the menu, a handwritten poem, scrawled on the back of another menu, had been pasted:

After we defeat Ernie Terrell

He will get nothing, nothing but hell,

Terrell was big and ugly and tall

But when he fights me he is sure to fall.

If he criticize this poem by me and Miss Moore

To prove he is not the champ she will stop him in four,

He is claiming to be the real heavyweight champ

But when the fight starts he will look like a tramp

He has been talking too much about me and making me sore

After I am through with him he will not be able to challenge Mrs. Moore.

The poem was penned one afternoon by Marianne Moore, the precise and witty modernist poet, and Muhammad Ali. It was George Plimpton who brought the two together. Throughout his life Plimpton easily inhabited the worlds of sports legends and literary elites. Moore, who was 79 at the time, had accompanied him to various events, not so much for the sport itself but for the spectacle and the details. (“One saw something of the poetic process while sitting with her,” Plimpton wrote.)

“We will call it ‘A Poem on the Annihilation of Ernie Terrell,’” Plimpton recalled Moore announcing.

In an interview Terrell had referred to Ali by his given name, Cassius Clay, and Ali was incensed. A few weeks after co-writing the poem, Ali met Terrell in the ring in what would come to be known as the “What’s my name” fight, for after every round Ali, pummeling Terrell, asked him, “What’s my name?”

Everyone knew Muhammad Ali’s name, especially after the Terrell fight. And everyone seemed to know Plimpton’s name, whether they read his books or not. Plimpton was an omnipresence for much of American cultural life—both high and low—in the last third of the 20th century. He appeared in commercials for Oldsmobile and Intellivision, and appeared in the movies The Bonfire of the Vanities and Good Will Hunting and on TV’s Married with Children. He was present when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated, helping to tackle Sirhan Sirhan. He turned up as a character on The Simpsons. In a New Yorker cartoon from 1967, a man about to undergo surgery looks up at the doctor wearing a mask and asks, “Wait a minute! How do I know you’re not George Plimpton?”

That Zelig-like identity rested largely on a series of seven books in which the New York–born, Harvard-educated Plimpton threw himself both physically and intellectually into the professional sporting life. Decades before the onset of reality TV and the Twittersphere, Plimpton starred in his own Everyman story. And this year Little, Brown is reissuing all seven stories on the 50th anniversary of the most famous of the series, Paper Lion: Confessions of a Last-String Quarterback.

Along with Paper Lion are books—and enhanced e-book versions—on Plimpton’s experiences with baseball (One for the Record and Out of My League), hockey (Open Net), golf (The Bogey Man), boxing (Shadow Box), and football (Mad Ducks and Bears). With introductions by Mike Lupica, Bob Costas, Denis Leary, Jane Leavy, and Steve Almond, this series will introduce the erudite enthusiasms of Plimpton to a new generation of readers and sports fans.

Paper Lion, like the other sports books, came out of articles he wrote for Sports Illustrated, and here Plimpton, after approaching several football teams, convinces the Detroit Lions to take him on. He describes showing up at the private-school campus where the Lions are training. The 36-year-old writer pulls into the driveway of a boys’ boarding school called Cranbrook in a rented convertible. At the registration desk he is mistaken for a member of the other group there—Episcopalian bishops, in town for a convention.

“There are people who would perhaps call me a dilettante,” Plimpton once said, “because it looks like I’m having too much fun. I have never been convinced there’s anything inherently wrong in having fun.”

What resulted from his fun was a first-hand account of what happened on the line of scrimmage—a view that fans were not otherwise afforded at the time.

“Plimpton wrote Paper Lion,” Nicholas Dawidoff says in the book’s introduction, “in what was still a Walter Mitty era of armchair fandom when from the bleachers all reveries were plausible.” The private-school setting of Paper Lion, according to Dawidoff, highlighted “that central juxtaposition of an amateur among professionals, elitist intellectual amid hard-hat muscle.”

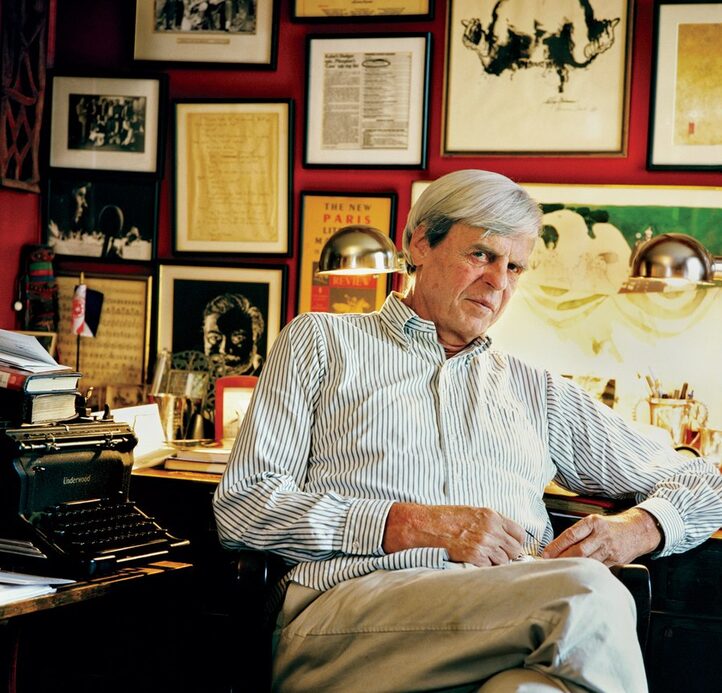

Plimpton’s second wife, Sarah Dudley Plimpton, to whom he had been married 12 years when he died in 2003, recently showed me around the same Upper East Side town house where Plimpton lived since the 1950s, when he was renting an apartment in the building. It was there, with views of the East River, where Plimpton threw his famous parties for theParis Review. Sarah directed me to a room with a desk and lined with bookshelves. Most everything had been filed and collected in plastic bins—his boxing gloves, the red leather faded and cracked; the robe that Ali wore, which, though his name is stenciled on it, actually feels like it had been taken from a Holiday Inn; Plimpton’s football cleats, which had been bronzed; his chair, wood with worn leather. She showed me the Toots Shor menu with the Ali-Moore poem.

Sarah Plimpton reached for one of the plastic bins on the shelves labeled “Paper Lion”—notebooks, a letter from Jack Mara, former president of the New York Giants, politely denying Plimpton’s request to train with the team, and photos. There is one of Plimpton stretching out on the practice field. He’s long and lanky, and showing a bright smile to the camera—obviously having fun. The photo has long been fused to the glass, though the frame is gone. The photo, she explained, was recovered from a Dumpster. “The co-op was cleaning out the basement,” said Sarah Plimpton. “I thought I better look and see what they’re throwing in there.” She also retrieved videos of interviews and movies that would later be used in Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself, a 2014 PBS American Masters documentary, as well as in Little, Brown’s trailer to the book series.

Perhaps Plimpton’s toughest act of participatory journalism was playing goalie for the Boston Bruins in the 1977 to 1978 season. The book that resulted was Open Net: The Professional Amateur in the World of Big-Time Hockey, which wasn’t published until 1985. Plimpton was nearly 50 years old and, by his own admission, could barely move on the ice: “I am very poor on skates. I tend to skate on my ankle bones.”

“He was not a young man,” said Sarah, looking at a picture of him. “He would not have characterized Open Net as being exciting. More exhausting.”

By book’s end, he finds himself playing five minutes in an exhibition game against the notoriously brutal Philadelphia Flyers, who had earned the nickname the “Broad Street Bullies.” With the Lions, Plimpton wore the number zero. The Bruins assigned him double zeros. He played alongside some of Boston’s greatest players, like Gerry Cheevers andTerry O’Reilly, and was coached by Don Cherry, now best known as a flamboyantly dressed and outrageously opinionated Canadian TV hockey commentator.

At one point, Bruins defenseman Mike Milbury threw his stick, and the Flyers were awarded a penalty shot. Reggie Leach drove toward the net and, miraculously, Plimpton kicked away the puck. The Bruins skated over to congratulate him and lead him off to the bench—and, in true amateur form, Plimpton slips and falls. The game goes on without him. But, no matter, for he had done what millions of sports fans could only dream of—to play amongst the greatest athletes, and then share that experience with his readers.

SOURCE: http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2016/04/george-plimpton-sports-books